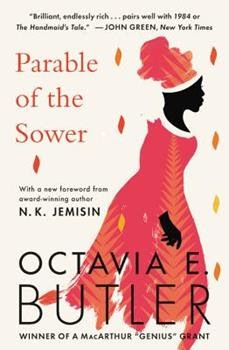

(image from Grand Central Publishing)

(image from Grand Central Publishing)

“Butler uses African American history… as a synecdoche for the cycling of racism and sexism throughout all of human history. Butler offers the story of Lauren Olamina and Earthseed as a parable for how we might avoid the "boomeranging" of history. Thus, she teaches us as readers both important lessons about history as well as techniques we might use to survive through the impending environmental, societal, and economic crises that are destined to evolve as a result of our current actions (or inactions)” – Marlene D. Allen

What does Octavia E. Butler’s Afrofuturist novel Parable of the Sower offer to teachers and students of interdisciplinary legal studies? In this post, we draw on our experience as student and teacher in an African American Political Thought course at SUNY Plattsburgh in Fall 2020 in order to articulate how Butler’s novel can be an animating text for studying law and justice. It is not new for many of us to consider the relations between law and literature, law and narrative storytelling, or law and lived experience. With these dynamic discourses in mind, we claim that Butler’s apocalyptic yet utopian speculative fiction is a unique text for legal studies students in its ability to compel readers to reimagine their understanding of and relationship to structures and experiences of oppression, racism, sexism, economic exploitation, climate catastrophe, religion, the state, and ultimately of visions of a more just future.

The late scholar of African American literature Gregory J. Hampton summarizes the novel thusly:

Parable of the Sower is both a travelogue narrative and a sort of bible all in one. … In the first section of Parable, entitled "2024," we learn that America has developed new drugs, colonized Mars, and deteriorated into some kind of capitalistic by-product, where "politicians and big corporations get the bread," and the proletariat gets close to nothing. Middle-class people have been forced to surround themselves with protective walls, and the unskilled masses are left as scavengers on the streets of what was once thriving metropolitan areas. It is through [protagonist] Lauren [Olamina’s] observations and opinions about the state of her world and its gods that she begins to construct Earthseed: The Book of the Living. Earthseed is Lauren's formulation of parables that outline a religion that identifies God as change and seeks to propagate itself and humanity throughout the stars.

In this post, we elaborate how this untimely world and ethical journey created by Butler proves edifying for students of law and justice.

Parable of the Sower will challenge students to think beyond their personal beliefs and what they know. In the long run, it can prepare them for their fight for justice; this is important for any individual looking to enter the legal field and seeking that laws should be applied fairly. Furthermore, the book expands its readers’ interpretation skills through the way it provokes deeper evaluations of daily circumstances. The novel engages numerous topics, such as religion, climate catastrophe, police brutality, racial capitalism, and so on. Discussions involving these issues often cause an individual to automatically turn towards their own views, but Butler implements them in a way that pushes readers to question how close their reality is to the dystopia presented in the novel.

Interpretation plays a vital part within law, and specifically in constitutional law. For example, precedent refers to previous court cases and rulings that have been made to set the authoritative standard for future cases dealing with the respective dispute. When looking at major landmark Supreme Court cases and the development of the Court’s interpretation of certain amendments (i.e. the commerce clause, necessary and proper clause, enumerated powers, scope of the Fourteenth Amendment, etc.), it is essential to be able to analyze the interpretive frameworks used by successive Justices and track change over time. As time progressed and societal views started to develop, the justice’s interpretation of constitutional laws began to change as well and it was evident within the court decisions. Parable of the Sower challenges readers to decipher, analyze, and acknowledge how society has fallen into a chaotic dystopia. When engaging in judicial interpretation and analysis, those skills can be applied in order to determine whether or not there has been a significant change to the conditions leading to earlier rulings, and to the anticipated consequences of future rulings.

Alongside building the ability to interpret different ideals, the novel will also expose the reader to oppression in a different light. As stated before, the novel addresses numerous social issues in a non-traditional--at least for many legal studies classrooms--manner. By basing the genre of the novel around science-fiction and placing the setting in the late 2020s, it opens the reader to receiving the social critique the novel presents. When issues such as racism, political corruption, and so on are presented in speeches, essays, journal articles and other non-fiction methods, people who are in a place of privilege and structural power are likely to automatically become defensive and can thus misinterpret, downplay, or ignore the message and purpose of the piece of writing. Fiction may allow a reader to reimagine their reality. For those who are privileged (i.e. males, whites, heterosexuals, able-bodied persons, etc.) reading fiction will assist in the process of acknowledging the different layers of oppression that prevail within the justice system and society overall.

To take one example of the way Butler opens up her readers to interrogating forms of oppression and exploitation, in the novel, racism and economic exploitation constitute one another. We suggest that Butler’s novel elaborates and illustrates the dynamics of racial capitalism, a theory that Georgetown philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò—drawing on the foundational work of political theorist Cedric Robinson, among others--articulates as analyzing how capitalism “came tethered to a wider set of social arrangements that tended to organise populations into sharp, vertical hierarchies.” These hierarchies “were cemented and maintained by material relations of domination” and by global “forms of social organization,” and continue to operate. Butler challenges her readers to consider how racism and disaster capitalism function together in her projection of 2020s America, a projection that reanimates past forms of oppression.

Here, a central moment in the first half of the book is Lauren’s diary entry about the buying out of the nearby town of Olivar by an international firm and its transformation into a privatized, hyper-securitized company town, in which people labor for room, board, and miniscule salary, with labor stratified by race. What makes Olivar’s privatization—a system Lauren calls “debt slavery” and her father calls “half antebellum revival and half science fiction” (122) possible? Lauren tells us that “labor laws, state and federal, are not what they once were” (121).

Later in the novel, Lauren’s emergent community is joined by a multiracial woman and her daughter, at which point Lauren narrates their experience escaping from a system of debt slavery more extreme than that in Olivar (287-88). Twice, Lauren makes explicit connections between racialized economic oppression in her time and American chattel slavery (218-19; 292). Near the conclusion of the novel the members of the fledgling community discuss how there are increasingly only two kinds of labor: slaves and slave drivers; one of the only alternatives is factories on the US-Canadian border featuring terrible pay and dangerous working conditions (323-24). More broadly, Butler’s novel illustrates the ways that economic, social and environmental collapse disproportionately endangers and exploits BIPOC, and how the logics of these large-scale crises are racialized; this is especially significant for thinking through the racialized impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The novel asks us as readers to consider all of this on both a structural and experiential level, provoking us to consider how we see racial capitalism operating in our own world.

Butler connects her interrogation of racial capitalism with a critique of policing as practiced in the context of deregulation and privatization. Lauren narrates police in the universe of Parable as responding late to any calls from impoverished areas (71); as requiring payment to perform even perfunctory investigations of crimes (19; 71; 316-18) as planting evidence in order to “solve” cases (114); as stealing from crime victims (246); and as at best doing nothing to redress—and frequently exacerbating—the ever-present violence committed against poor and racialized communities (51; 229; 236-37). The way Butler ties police violence to broader socioeconomic collapse resonates with analyses in the framework of racial capitalism. The novel thus offers the reader a speculative standpoint on our contemporary debates about race and police violence, a standpoint offering both a systemic critique and an experiential literary account of racialized policing.

These are not the only ways that Parable of the Sower speaks to issues we are likely engaging in our classrooms. The novel also provides routes of entry into considering Black feminist analyses of ecology and environment, intersectional perspectives on disability, migration, race, and capital, feminist theories of power, the gendered and racialized body, and other pertinent questions. More broadly, Butler’s critique of the present and of the future draws on histories of racialized and gendered oppressions to examine time as cyclical, thus “denot[ing] the violent nature of the spiraling of history, especially for African Americans and other marginalized groups.” This has the effect of compelling us to question received notions about constant progress and linear development, and to wonder what dynamics, institutions, and oppressions in our present are leading us to catastrophe. Crucially, however, through Lauren’s cosmology-as-ethical-community Earthseed, Butler also articulates a vision of a just future that breaks out of historical, sociopolitical stasis to imagine what an intersectionally-minded human and environmental flourishing might entail, and what new worlds might (or must) be possible.

Amid the discussions we are having in our classrooms about racism and racial justice, COVID-19, climate catastrophes, demagoguery, the supposed breakdown of liberal democracy, inequality, individual rights, and the state, it enriches the analysis and critique of students and teachers alike to think with Octavia Butler.

Claudia Mei Theagene is a senior at SUNY Plattsburgh, majoring in Political Science and minoring in Africana Studies and in Legal Studies; John McMahon is Assistant Professor of Political Science at SUNY Plattsburgh and a member of the CULJP Board of Directors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed