Jinee Lokaneeta, Drew University

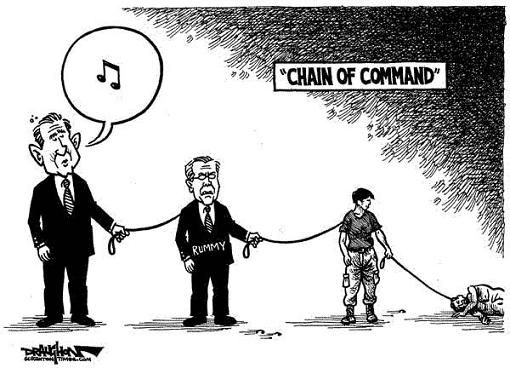

A Deeper Look at the Chain of Command within Abu Ghraib

By: Shaylyn MacKinnon, Brooke Winters, Sage Johnson, and Aurie Flores

In the interview with Angela Y. Davis, Davis asserts that “these abusive practices [at Abu Ghraib] cannot be dismissed as abnormalities,” echoing sentiments that reject the ‘few bad apples’ explanation put forward by the U.S. government in the early days of the Abu Ghraib scandal (49). Moreover, this cartoon ties in with Basuli Deb’s work regarding the tensions between liberal feminism and transnational feminism after the Abu Ghraib atrocities. Deb writes that “US-centric feminisms at once leapt to the rescue of these women [such as Lynndie England] and portrayed them merely as tools manipulated by the military establishment” (Deb, 1). Transnational feminism, on the other hand, looks at the dynamics between gender and race, taking note of how white women became ‘good citizens’ by helping in the torture of brown Iraqi detainees. This cartoon highlights the transnational feminist perspective by showing that while Lynndie England was working for the higher up government apparatus, she is also accountable for her part in the chain of command. England, though being a woman and a victim of the patriarchy, is white and therefore benefits from that patriarchy due to the power she holds over men of color.

Looking into the actual illustrative details of the cartoon, the themes mentioned (lack of accountability and where responsibility lies in the chain of command for torture) are represented most clearly in the directions each figure is facing. Lynndie England, the lowest in the “Chain of Command” and the one who was directly involved in the torture, faces the crumpled figure of the torture victim head on, thus acknowledging her actions in the practice of torture. On the contrary, Rumsfeld's head is only slightly angled toward England, giving the impression that he is neither acknowledging nor condemning the actions that led to the crumpled and chained figure. President Bush’s face is turned the furthest from the body, his eyes closed, whistling a tune to represent how he refuses to outwardly acknowledge the torture in any way. The positions of power are indicated by the size of each character, Bush by far the largest with each body shrinking in scale as the chain. While the size decreases, the detail of each figure increases the closer they get to the tortured victim, again suggesting a refusal to acknowledge the extent of the torture the further up the command chain one is. England is the most detailed because the public has become privy to the details of her involvement in the torture, whereas Bush and Rumsfeld’s connections are obscured to the public, leaving them “clean”. This cartoon is significant to the contemporary public because of its deconstruction of the ‘few bad apples’ explanation.

References

Angela Y. Davis. Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and Torture. Seven Stories

Press, 2005.

Basuli Deb. “Transnational Feminism and Women Who Torture: Re- imag(in)ing Abu Ghraib

Prison Photography.” Postcolonial Text 7. 1, 2012.

Drughon, Dennis. “Chain of Command.” Scranton Times, Scranton Times, 16 May 2004.

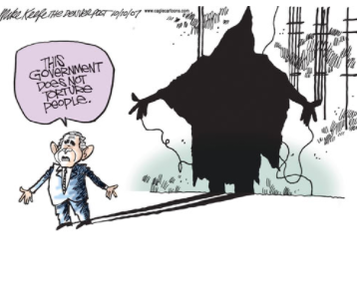

“The Shadow”

By: Brielle Castanheira, Alex Gilgorri, Dalton Valette, Boshudha Khan, Sebastian Godinez

References

Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Translated by Alan Sheridan.

New York: Vintage Books, 1977.

Keefe, Mike. “The Denver Post .” The Denver Post , The Denver Post, 2007.

Lokaneeta, Jinee. Transnational Torture: Law, Violence, and State Power in the United States

and India. New York University Press, 2016.

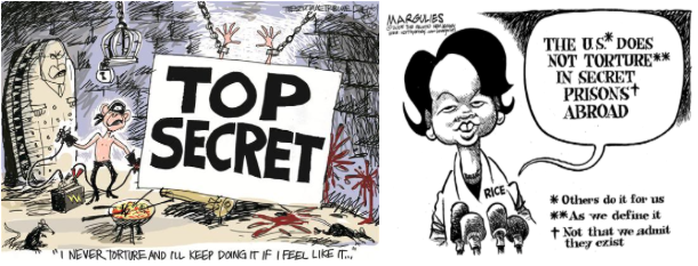

“The Faces of Denial”

By: Luis Leroux, David Rosenblum, Nick Defuria, Megyn MacMullen

References

Lokaneeta, Jinee. Chapter 1: “Law’s Struggle with Violence: Ambivalence in the “Routine”

Jurisprudence of Interrogations in the United States” in Transnational Torture.

Fiore, Mark. “Top Secret.” 17 November 2005.

Margulies, Jimmy. “Rice Decries Torture.” The Comic News. 14 December 2005.

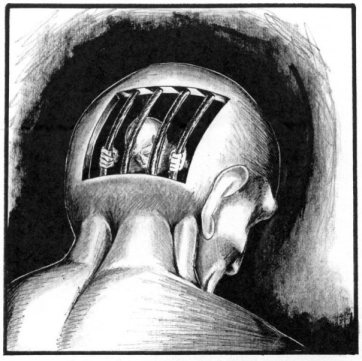

Internal Imprisonment

By Mariia, Sam, Marta

Some of the themes we related this political cartoon to were the transition from the spectacle of torture to a more private form of torture, specifically Foucault's idea that torture has become about imprisonment and detainment. Furthermore, this cartoon shows the more modern psychological form of torture. This is shown in the way he seems to be imprisoned within his own mind. This cartoon could also be demonstrating an after effect of torture in that the effects never leave and the tortured experiences post traumatic stress. Even though he may be free, torture and pain can be hard to describe with words and the experience leaves him trapped with his memories. In a contemporary sense we related this to the U.S. and its current detainee program in which they often deprive detainees of their senses using blindfolds and earmuffs leaving them only with their own thoughts. Prolonged exposure may lead to the detainee having mental issues and effectively “going crazy” from being trapped with only their own thoughts.

References

Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Translated by Alan Sheridan.

New York: Vintage Books, 1977.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed